Review »Solidarisch mit Seeigeln«

Von Hans-Joachim Müller, DIE WELT, 17. Januar 2015

»nature after nature«, Susanne M. Winterling

Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel, 11. Mai 2014

Review »Susanne M. Winterling«

Von Chris Kraus, ARTFORUM, 21. Mai 2014

von Birgit Kulmer, Kunsttexte.de 2/2010

»Isadoras Schal«

von Birgit Kulmer, Parrotta Contemporary Art

Mit ihrer eigens für die Galerie entstandenen Installation „Isadoras Schal“ unternimmt die in Berlin lebende Künstlerin eine eigensinnige Relektüre der Moderne und ihrer Ikonen. Sie verwebt in ihrer installativen und fotografischen Arbeit widerspruchsvolle Momente wie Technik versus Körper, Artifizialität versus naturhaftem Ausdruck, Mystizismus versus Rationalität und unterläuft damit überkommene Dualismen des Diskurses der Moderne. Charles Baudelaire hat in seinem Essay „Le peintre de la vie moderne“ (1863) den Bergriff der „modernité“ mit den Eigenschaften des „Wandels“ (le transitoire), des „Flüchtigen“ (le fugitif) und des „Zufälligen“ (le contingent) verbunden. Damit sind nicht nur Kriterien der Bestimmung des Modernen benannt, sondern diese Merkmale kennzeichnen zugleich die Kunst des Tanzes, die auch Thema bei „Isadoras Schal“ ist. Die formal strenge Schwarz-Weiß-Gestaltung des Ausstellungsraumes wird mit „Isadoras Schal“ zum Hintergrund einer Bühnenkonstruktion, die in ihrer reduzierten Gestalt als bewegliches schwarzes Quadrat eine Gruppe von Puppen in konstruktivistisch anmutenden Kostümen trägt. In ihrer geometrisierenden Formensprache evozieren jene Kasimir Malevichs Kostüme der futuristischen Oper „Sieg über die Sonne“. In einer kürzlich im Le Corbusier Haus „Unité d’Habitation (Type Berlin)” von Susanne M. Winterling inszenierten Performance „On the displays of light, inside and outside – there might be no victory over the sun” kamen diese Kostüme bereits zum Einsatz. Die schwarzen Verkleidungen mit ihren kantigen Auswüchsen ließen die Körper der jungen Mädchen, auf die sie zugeschneidert waren, noch fragiler und formbarer erscheinen, als es ihr Alter ohnehin schon mit sich bringt.

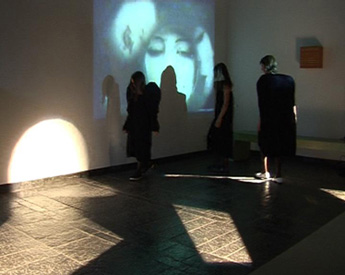

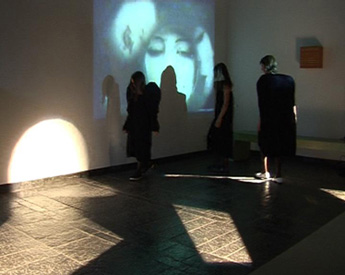

„On the displays of light, inside and outside – there might be no victory over the sun”, im: Le Corbusier Haus „Unité d’Habitation (Type Berlin)”, im Rahmen der 5. Berlin-Biennale.

Mit ihrer Stuttgarter Installation knüpft Susanne M. Winterling darüber hinaus an Oskar Schlemmers „Triadisches Ballet“ in der Stuttgarter Staatsgalerie an. Dies insofern als die Tänzerinnen auf der angedeuteten, der Zuschauerränge entbehrenden Bühne abwesend und durch Puppentorsi ersetzt sind. Schlemmer beschreibt die Kostüme seines Triadischen Balletts als „ein Zwischenglied zwischen absoluter unmenschlicher Marionette und der natürlichen menschlichen Gestalt“. Der Mensch, insbesondere jedoch der tanzende Mensch, galt auch der Wegbereiterin modernen, freien Tanzes Isadora Duncan als Repräsentant einer höheren Ordnung, jedoch nicht als mathematisch-geometrisch bestimmbarer Typus wie bei Oskar Schlemmer, sondern als ein „natürlich“ gedachter Körper in seiner Einheit aus Physis und Psyche. Isadora Duncan, auf die Susanne M. Winterling mit dem Ausstellungstitel explizit Bezug nimmt, gehört zur ersten Generation von Tänzerinnen, die sich von der Position des rein ausführenden Objektes verabschieden und sich Raum für ihre eigenen Vorstellungen vom Tanz erkämpfen. Jenen verstand sie nicht nur als Kunst, sondern auch als Mission zur "Heilung zivilisatorischer Schäden". Sie lehnte den starren Formenkanon des traditionellen Balletts ab und stellte ihren als „natürlich“ gedachten Körper in den Mittelpunkt eines improvisierten Tanzes – ohne Korsett, ohne Spitzenschuhe – sondern barfuß in einer hellenistisch anmutenden Robe, zu der auch ihr fließender Seidenschal gehört. Sie orientiert sich dabei an antiken Abbildungen von Tanz – und Alltagsszenen und übernimmt deren Bewegungseigenheiten. Sie gründet Tanzschulen, die erste 1904 in Berlin, in denen sie ihre Schülerinnen, für deren Kost und Logis sie aufkommt, zu freien Menschen erziehen möchte.Von Isadora Duncans Tanz, der wie jeder Tanz eine Kunst des Augenblicks ist, gibt es so gut wie keine Aufzeichnungen – lediglich durch die Fotokamera, die ihn still stellt – zu Posen gefrieren lässt. Dieser Liaison aus Tanz und Fotografie unterliegt eine eigentümliche Nähe aus Tanz, Vergänglichkeit und Tod. Diese Nähe wird durch den Titel der Ausstellung „Isadoras Schal“ noch hervorgehoben, denn dieser wurde der Tänzerin zum tödlichen Verhängnis, als er sich in den Radspeichen eines Bugattis verfing und sie zu Tode strangulierte.Damit stellt die Bühnenkonstruktion, drehbar um den zentralen Pfeiler des Raumes, den historischen Kern, oder mehr noch, ein fein gesponnenes Netz aus historischen Bezügen, Referenzen und Zitaten dar, das stets auch die persönliche und familiäre Geschichte der Künstlerin integriert und damit im Hier und Jetzt ankert. Die Unauflösbarkeit des für den Betrachter ausgelegten Netzes aus Bezügen, der sich immer wieder verwirrenden Fäden, entspricht dabei einer künstlerischen Methode, die gegenüber der hier von Susanne M. Winterling zitierten avantgardistischen in Zweifel zieht, man könne zu Pudels Kern oder zum „Schwarzen Quadrat“ tatsächlich vordringen, ohne einen Teil der Wahrheit auszublenden. So beschneidet ein offener Kreis, der zugleich den Bezug zum Ausstellungsraum herstellt, das schwarze Quadrat der Bühne und lässt es als unvollendet erscheinen. Denn: „On the displays of light, inside and outside—there might be no victory over the sun”. Die Fotoserie „Die Drehung um sich selbst“ (2008) zeigt Aufnahmen aus einer Berliner Ballettschule, welche die Künstlerin über einen längern Zeitraum immer wieder besuchte, um eine gewisse Vertrautheit der Mädchen mit dem Beobachtet-Werden durch die Kamera zu erreichen. Auf den Fotografien erscheinen die Körper der Mädchen durch die relative Langzeitbelichtung in ihrer Bewegtheit teilweise verschleiert und in ein sanftes goldenes Licht getaucht. Sie bilden damit einen Gegensatz zur Starre der Bühnenkonstruktion mit ihren schwarz kostümierten Puppen. Ihre Bewegungen erscheinen leicht, als ließe sich in diesem geschlossenen Universum der Tanzschule tatsächlich ein Freiraum ertanzen – ganz im utopischen Sinne der Tanzpädagogin Isadora Duncan. Die Videoinstallation „Secret Writing III“ (2006) am Ende eines ansteigenden, dunklen Ganges zeigt eine im Entstehen begriffene Geisterhandschrift, die da wie ein Lehrer mit weißer Kreide auf eine schwarze Tafel zu schreiben scheint: „It does not exist if it is not framed“. Der Gedanke an Derridas Aufsatz „Parergon“ (Beiwerk/Ornament) in “Die Wahrheit in der Malerei” kommt auf. Der Text nimmt als Ausgangspunkt Kants Charakterisierung des Rahmens in seiner „Kritik der Urteilskraft“, nicht als essentielles Element, sondern als eine externe Hinzufügung - Parergon. Nach Kant macht der Rahmen, die Gestalt des eigentlichen Werkes (Ergon) nur deutlicher, definitiver und komplett und zieht die Aufmerksamkeit auf das, was im Inneren des Rahmens geschieht – den Inhalt. Dies, so stellt Derrida fest, macht den Rahmen allerdings zu einem ganz und gar unersetzlichen Ornament – das heißt zu einem konstitutiven Element. Denn erst der Rahmen macht das Werk eigenständig (autonom) innerhalb des Feldes der Sichtbarkeit und bestimmt damit die Bedingungen der visuellen Rezeption. Durch den Rahmen ist ein Bild niemals nur ein Ding unter anderen, sondern er macht es zum Objekt der Kontemplation. Für Derrida antwortet der Rahmen auf ein signifikantes und prinzipielles Fehlen im Werk selbst. Dieses Fehlen macht das “framing” notwendig und nicht nur ornamental und beliebig, wie Kant annimmt, sondern essentiell. Tatsächlich rüttelt Derrida an der Hierarchie von Werk und Rahmen um, ohne eine neue Opposition aus Werk und Nicht-Werk zu etablieren, beide Seiten durch den Verweis auf Paradoxa ihrer Seinsweise in ein dynamisches Verhältnis zu versetzen.Diese bestehen darin, dass der Rahmen das Werk von seinem Kontext zu separieren sucht und dabei ein Objekt durch seine Umhüllung unserer Aufmerksamkeit zuführt, die es sogleich als Kunstwerk versteht und ihm daher einen Bedeutungsgehalt zuschreibt. Der Rahmen löst sich in Bezug auf das Werk im allgemeinen Kontext auf, in Bezug auf den Kontext jedoch löst es sich quasi im Werk auf. Von daher scheint der Rahmen eigentlich vollends zu verschwinden, da er keinen Ort besitzt. So schlägt Derrida vor, nicht mehr von „frame“, sondern nur noch von „framing“ in seiner aktiven Form beziehungsweise von „frame effects“ zu sprechen. „Es gibt Rahmen, aber der Rahmen existiert nicht.“ Insofern kann Susanne Winterlings Videoarbeit, die das Verschwinden des Rahmens zum eigentlichen Thema hat, auch als eine zeitgenössische Neuformulierung von René Magrittes „Ceci n´est pas une pipe” gelesen werden, mit welcher sie formal die naiv anmutende Handschrift auf schwarzem Grund teilt. Während Magritte sich auf die unschließbare Lücke zwischen dem Objekt und seinem Abbild konzentriert und die unvereinbaren Möglichkeiten der Lesbarkeit seiner Darstellung vorführt und schließlich kollabieren lässt, konzentriert sich Susanne M. Winterling nun verstärkt auf das Medium und den Rahmen, jenseits der Darstellung als solcher. Ein auf die Galeriewand projizierter Videofilm, der diese immer wieder neu beschriftet, macht die rahmende Funktion des Ausstellungsortes anschaulich. Die hier wieder und wieder wie von Geisterhand beschrifteten Wände programmieren die Erwartungen der Besucher und disziplinieren ihr Verhalten. Susanne Winterling kehrt somit das “hermeneutic surplus” des Ausstellungsraumes hervor und unterläuft es sogleich, indem sie es zum Gegenstand der Reflexion macht.

Gabriele Brandstetter: Tanzlektüren. Körperbilder und Raumfiguren der Avantgarde, Frankfurt am Main 1995, 35.

Jacques Derrida: Die Wahrheit in der Malerei, (Va vérité en peinture, Paris 1978) aus dem Französischen von Michael Wetzel, Wien 1992, S. 103.

### ENGLISH VERSION ###

»Isadora's Shawl«

by Birgit Kulmer, Parrotta Contemporary Art

With her installation, "Isadora's Shawl " specifically created for the Gallery space, the Berlin based artist undertakes an opinionated rethinking of Modernity and its icons. In her installations and photography she weaves together contradictory moments, such as technology versus the body, artificiality versus natural expression, mysticism versus rationality and thus undermines traditional dualisms of the discourse of modernity. Charles Baudelaire in his essay "Le peintre de la vie moderne" (1863) connected the concept of "modernité" with the properties of the "the transient" (le transitoire), "the fugitive" (le fugitif) and the "the contingent" (le contingent). This describes not only the criteria determining Modernity, but these features also characterize the art of dance, which is as well a theme of "Isadora's Shawl". The strict formal black and white design of the exhibition space is in "Isadora's Shawl" a backdrop of a stage construction, reduced to the form of a maneuverable black square carrying a group of mannequins. Her geometric style evokes the thought of Kasimir Malevich's futuristic costumes from the opera "Victory over the sun". These costumes appeared recently at the Le Corbusier house "Unité D' Habitation (type Berlin)" in a staged performance produced by Susanne M. Winterling called "On the displays of light, inside and outside – there might be no victory over the sun". The black costumes with their chiseled appendage let the bodies of young girls, seem even more fragile and shapeable as their age already entails. Susanne M. Winterling ties her Stuttgart installation together with Oskar Schlemmer's "Triadisches Ballet" in the Stuttgart Staatsgalerie. In this respect the stage is implied, the seating for the audience is absent and the dancers are replaced by mannequins. Schlemmer describes the costumes of his Triadic Ballet as "a link between absolute inhuman puppet and the natural human form." Humans, in particular dancing humans, according to Isadora Duncan, are considered representatives of a higher order; she was considered the pioneer of modern, free dance, not defined however as a mathematical-geometric type like Oskar Schlemmer, but rather thought of as a "natural" body in its oneness of physique and psyche. Isadora Duncan, to which Susanne M. Winterling refers to explicitly with the exhibition title, belonged to the first generation of dancers, who moved away from the position of being purely a performing object and fought for a space for their own ideas of dance. Regarding this, they understood it not only as art, but also as a mission to "heal a damaged civilization". She rejected the rigid framework of the canon of traditional ballet and introduced her "natural" body in the center of an improvised dance - no corset, no pointe shoes - but barefoot in a Hellenistic-style robe, to which her flowing silk scarf belongs. She oriented herself to the ancient images of dance - and everyday life scenes taking over their movement peculiarities. She founded dance schools,the first in 1904 in Berlin, where she taught for free and paid for the room and board of her pupils. Isadora Duncan's dancing was like any dance - an art of the moment, from which there is as good as no documentation - only taken by camera, seeming to stand still- poses that are frozen. This Liaison of dance and photography underlies a peculiar closeness with dance, transience and death. This proximity is accentuated by the title of the exhibition "Isadora's Shawl", because this is what brought the dancer to her fatal death, when her scarf got caught in the wheel spokes of a Bugatti car and strangled her to death. Thus the stage construction, swivelling over the central column in the space, symbolizes the historic core, or even more so- a finely spun web from historical implications, references and quotations, which also integrates the personal and family history of the artist and thus anchors it in the here and now. The durable weave of the network of implications for the observer, which is again and again a thread that gets tangled up, corresponds to the artistic practice of Susanne M.Winterling who is cited doubting the opposite method to hers- that of the avant-garde, in which one could indeed advance towards "des Pudels Kern" (the crux of the matter) or to the "Black Square", without blocking out a bit of the truth. So an open circle, which is a reference to the exhibition space, cuts the black square on the stage making it seem unfinished. Because: "On the displays of light, inside and outside, there might be no victory over the sun".

"On the displays of light, inside and outside - there might be no victory over the sun", in: Le Corbusier Haus "Unité d'Habitation (Type Berlin)", at the 5th Berlin Biennial.

The photo series "Die Drehung um sich selbst" (2008) shows photographs from a Berlin ballet school, which the artist visited repeatedly over a long period time in order to obtain from the students a certain level of confidence in front of the camera. In the photographs the bodies of the girls appear, through the relatively long exposure time, partially veiled in their movement and plunged into a soft golden light. They form thereby a contrast to the rigidity of the stage construction with its black costumed mannequins.Their movements appear easy, as if in this closed universe of the dance school they were actually dancing to achieve freedom - in the complete Utopian sense that Isadora Duncan taught.

The video installation "Secret Writing III" (2006) projected at the end of a rising, dark corridor shows a emerging ghost hand writing: "It does not exist if it is not framed" appearing like a teacher writing with white chalk on a blackboard. The thought of Derrida's essay "Parergon" (accessories/ornament) comes to mind from "The Truth in Painting". The text takes as its starting point Kant's characterization of framework in his "Critique of the Power of Judgment", not as an essential element but rather as an external addition - Parergon. According to Kant, the framework makes the shape of the actual work (Ergon), more clear, definitive and complete drawing attention to what is done inside of the framework - the content. This, determines Derrida, makes the framework, however, an utterly irreplaceable ornamentation - that is a constitutive element. Because only the frame makes the work independent (autonomous) within the field of the visibility and determines thereby the conditions of the visual reception. Through the frame a picture is never just one thing among others, but rather it makes it the object of contemplation. For Derrida the framework answers to a significant and principle absence in the work itself. This absence makes "framing" necessary and not only ornamental and arbitrary, as Kant assumes, but essential. Indeed Derrida shakes up the hierarchy of work and framework, without establishing a new opposition from the work and non-work, to transfer both sides by reference to the paradox of its being into a dynamic relationship. This consist in the fact that the frame seeks to separate the work from its context and thereby grabs our attention to an object through its encasement, which one understands immediately as a work of art and is able to attribute meaning to it. The framework resolves itself in relation to the work in a general context, however in relation to the context it resolves itself in the work. Hence the frame actually seems to disappear completely, because it has no place. So Derrida proposes to speak no longer about "frame", but rather only of "framing" in its active form or to be precise, of "frame effects". "There is framing", says Derrida, but the frame does not exist. To the extent that Susanne Winterling's video work, has the disappearance of the frame being the actual subject, it can be read, also as a contemporary formulation of René Magrittes "Ceci n´est pas une pipe", with which it shares the same naively seeming handwriting on a black background. While Magritte concentrates on the space that one is not able to fill between the object and its image and demonstrates the incompatible possibilities of the legibility of its representation, and lets it collapse in the end, Susanne M. Winterling concentrates now on reinforcing the medium and the frame, beyond the representation as such. A video film project on the gallery wall, which consists of this handwriting written over and over, makes the framing function of the exhibition space clear. Here again and again the ghost handwriting on the wall programs the expectations of visitors and disciplines their behavior. Susanne Winterling thus reverses the "hermeneutic surplus" of the exhibition space and immediately undermines it by making it the subject of the reflection.

Gabriele Brandstetter: Dance Readings. Body images and figures of the avant-garde space, Frankfurt am Main 1995, 35

Jacques Derrida: The Truth in Painting, (Va vérité en peinture, Paris 1978) from the French by Michael Wetzel, Vienna 1992, p. 103

In: an.schläge – Das feministische Magazin, März 2009.

In: MOUSSE – contemporary art magazine, Februar/März 2009.

3 SUSANNE M. WINTERLING, EILEEN GRAY, THE JUWEL AND TROUBLED WATER, 2008.

In: Artforum International, Top Ten, Josef Strau, September 2008, S. 183.

5. berlin biennale für zeitgenössische kunst 5.04. bis 15.06.2008

When things cast no shadow

In: Monopol Magazin, April 2008.

Kunstbiennale Berlin

Was hinter der Faust haust

Von Niklas Maak, in: FAZ.NET

(...)

Architekturtheorie der Doppeldeutigkeiten

Susanne Winterling zum Beispiel hat die Garderobenkabinen ausgeräumt und in ihnen Objekte, Filme und Fotos zu einer suggestiven Architekturtheorie der Doppeldeutigkeiten arrangiert. Aufgelöste Formen, Wiedergänger, Nachbilder, halbscharfe Erinnerungen: alles, was in rationalistischen Bauvisionen keinen Platz hat, versammelt sich hier. (...)